Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

Ode to Death op.38 (H. 144) (1919)

London Symphony Chorus e City of London Sinfonia

diretti da Richard Hickox | DOWNLOAD

Multimedia Cards Including Rare Audio and Video

Gustav Holst (1874-1934)

Ode to Death op.38 (H. 144) (1919)

London Symphony Chorus e City of London Sinfonia

diretti da Richard Hickox | DOWNLOAD

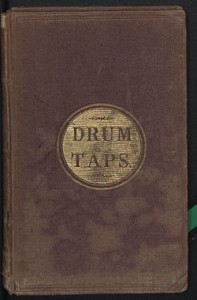

Whitman

Drum Taps

Original by Chris Shepard | Link to Source

One of the most hauntingly beautiful of the Whitman “death poems” is from Drum Taps. It is at the heart of Vaughan Williams’ Dona Nobis Pacem. As I said at the Sing-In on Saturday, one reason I am so fascinated with RVW’s setting is that it is a “palimpsest” of sorts—there are architectural layers beneath its more prominent placement in the oratorio.

Although Dona Nobis Pacem was written in 1936, this movement was composed as a free-standing composition in 1914, at the onset of World War I. For some reason, I happen to be reading a couple different books that discuss WWI at the moment, and I’m especially aware of the idea that many villages sent virtually all of their men—of two generations—off to fight, often belonging to the same fighting unit. In this way, entire towns lost an unthinkable percentage of their men in the slaughter in the fields of Belgium. Vaughan Williams was clearly thinking of this as Germany was mobilizing for war in the mid 1930s, and as Mussolini was coming to power in Italy—that the unthinkable might, unthinkably, be repeated.

But there is another archeological layer to this composition: the poem itself. Whitman released this poem as part of his mighty Drum Taps, written throughout the war and published first in 1865, and then as part of a revised edition of Leaves of Grass (itself first published in 1855) that Whitman produced in 1867. Like World War I, the American Civil War resulted in extraordinary numbers of casualties, eclipsed in American warfare only by World War II. And again, so great was the need for soldiers that often two generations were lost, not just young men in their late teens and early twenties.

In this way, Vaughan Williams’ setting of Dirge for Two Veterans is a complex and rich tapestry of grief, encompassing the mourning of three wars and two major artists. Here is Whitman’s poem:

The last sunbeam

Lightly falls from the finished Sabbath,

On the pavement here, and there beyond it is looking

Down a new-made double grave

Lo, the moon ascending,

Up from the east the silvery round moon,

Beautiful over the house-tops, ghastly, phantom moon,

Immense and silent moon.

I see a sad procession,

And I hear the sound of coming full-key’d bugles,

All the channels of the city streets they’re flooding,

As with voices and with tears.

I hear the great drums pounding,

And the small drums steady whirring,

And every blow of the great convulsive drums,

Strikes me through and through.

For the son is brought with the father,

(In the foremost ranks of the fierce assault they fell,

Two veterans son and father dropt together,

And the double grave awaits them.)

Now nearer blow the bugles,

And the drums strike more convulsive,

And the daylight o’er the pavement quite has faded,

And the strong dead-march enwraps me.

In the eastern sky up-buoying,

The sorrowful vast phantom moves illumin’d,

(‘Tis some mother’s large transparent face,

In heaven brighter growing.)

O strong dead-march you please me!

O moon immense with your silvery face you soothe me!

O my soldiers twain! O my veterans passing to burial!

What I have I also give you.

The moon gives you light,

And the bugles and the drums give you music,

And my heart, O my soldiers, my veterans,

My heart gives you love.

Many composers have been drawn to this text, most notably RVW and his English compatriot Gustav Holst, who wrote a version of the same text for men’s choir, brass and drums in 1914. The first clip below is from Vaughan Williams’ Dona Nobis Pacem, conducted by Robert Shaw. Shaw had a special connection to the poetry of Whitman; it was he who commissioned and premiered one of the great twentieth-century choral works, Hindemith’s setting of When Lilacs Last in Dooryard Bloom’d. I had the great pleasure of seeing Shaw conduct the work at Yale only a couple years before his death—he was at the height of his powers, fully in command of the sprawling work. He brings a remarkable sensitivity to the text in this recording of the Dirge for Two Veterans with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. (Editor’s note: the Atlanta recording has been removed and replaced by the following.)

For comparison, I include here the Holst version. Some people have suggested that Vaughan Williams set the Dirge in friendly competition with Holst; they are certainly very different works, with RVW’s near-Impressionist colors in contrast to the Holst’s more martial version. This clip is particularly special to me—speaking of mourning, it is conducted by the late Richard Hickox, whom I met on several occasions in Sydney when he was music director of the Australian Opera. He was always extremely kind to me, and I was as shocked as the rest of the musical world when he died at a very youthful 60 in November 2008, just as I was moving back to America. Though he was a strikingly versatile conductor (I especially remember an extraordinary production of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsesnk that I saw him conduct), he had a special affinity for the English repertoire, as is clear from this recording.

Frederic Louis Ritter (1880)

Frederic Louis Ritter (1880)

Collected from the Library of Congress | Source

Bibliographical Note

via Special Collection at Vassar

Frédéric Louis Ritter, composer and music professor, was born in Strasbourg on 22 June 1834. His family name was Caballero, and his surname was translated from the Spanish word for “gentleman” to the German word for “knight.” Both evoke a similar chivalric ideal. Growing up in Alsace, Ritter was influenced by French and Germanic musical styles. He studied first with Hans M. Schletterer and [unknown] Hauser. Starting at the age of 16, he studied in Paris under the supervision of his cousin Georges Kastner. “Possessed with the idea that beyond the Rhine he would find better opportunities for the study of composition,” Ritter ran away to modern-day Germany. This was usual for serious students of composition at that time. Ritter returned to Lorraine in 1852, and soon accepted a position as professor of music at the Protestant Seminary of Fénéstrange. | Read more at Vassar College

Title: Dirge for two veterans | Ritter, Frederic Louis.

Notes- From: Music Copyright Deposits, 1870-1885 (Microfilm M 3500)

Also available through the Library of Congress Web Site as facsimile page images.

J.D. McClatchy on Walt Whitman’s “Drum-Taps”

Transcription of Commentary

This is J. D. McClatchy, and I’m recording this on June the 11th, 2012, in the midst of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. These four years the country is commemorating the terrible events of those days so long ago, and on June the 11th, 1862, the South was enjoying a series of stinging victories. And I have in front of me a copy of a letter that General Lee wrote to Stonewall Jackson saying,

General, your recent successes have been the cause of the liveliest joy in this army as well as in the country. The admiration excited by your skill and boldness has been constantly mingled with solicitude for your situation. The practicality of reinforcing you has been the subject of earnest consideration. It has been determined to do so at the expense of weakening this army.

And so on and so forth, as General Lee planned his great campaign.

The Civil War remains the most cataclysmic and tragic event in our history. Behind the struggle, driving its purpose and passions, loomed the greatest of issues: the fate of a country and the rights of its people. Hateful decisions were at the heart of the conflict. A Northern sense of justice and a Southern sense of honor, moral principle and emotional pride, drove men to their deaths amid the terrors of war—the deafening noise, the blinding smoke, the ground slick with blood, the cries of the fallen. Over 620,000 soldiers died during those four years, nearly as many as in all of America’s other wars combined. Proud cities were put to the torch, civilian populations were brutalized, fertile countryside was reduced to wasteland, brother fought against brother, and there was not a household in the land that did not have a loss to mourn. The very names of the fearsome battles and valiant commanders ring in people’s memories with the force of myth. The grandeur and pathos of the two shredded armies never failed to thrill. In the end, slavery would be abolished, succession defeated, and a new nation born in fire, blood, and sorrow. And each side in the conflict would discover its tragic hero: for the South, Robert E. Lee, whom I just quoted—the model Virginia gentlemen who fought for the lost cause with audacious skill and relentless determination; for the North, Abraham Lincoln, the martyred redeemer president who spoke for American democracy with an eloquence unmatched in our history. It is such stuff as epics are made on. And yet, it seems strange that no one great sweeping poem, no American Iliad, ever emerged from this most momentous event in the lives and imaginations of Americans.

Individual poets did write, of course, and we have as our substitute for an epic poem marvelous lyric takes and moral meditations by Herman Melville and, above all, Walt Whitman, whose collection in 1867 called Drum Taps brought together the poems he had written, both in the field and back in Washington, about episodes in the Civil War, in which he worked tirelessly as a nurse in the field hospitals. | MORE

Drum-Taps

Beat! Beat! Drums!

Beat! beat! drums!—blow! bugles! blow!

Through the windows—through doors—burst like a ruthless force,

Into the solemn church, and scatter the congregation,

Into the school where the scholar is studying,

Leave not the bridegroom quiet—no happiness must he have now with his bride,

Nor the peaceful farmer any peace, ploughing his field or gathering his grain,

So fierce you whirr and pound you drums—so shrill you bugles blow.

Beat! beat! drums!—blow! bugles! blow!

Over the traffic of cities—over the rumble of wheels in the streets;

Are beds prepared for sleepers at night in the houses? no sleepers must sleep

in those beds,

No bargainers’ bargains by day—no brokers or speculators—would they continue?

Would the talkers be talking? would the singer attempt to sing?

Would the lawyer rise in the court to state his case before the judge?

Then rattle quicker, heavier drums—you bugles wilder blow.

Beat! beat! drums!—blow! bugles! blow!

Make no parley—stop for no expostulation,

Mind not the timid—mind not the weeper or prayer,

Mind not the old man beseeching the young man,

Let not the child’s voice be heard, nor the mother’s entreaties,

Make even the trestles to shake the dead where they lie awaiting the hearses,

So strong you thump O terrible drums—so loud you bugles blow.

Cavalry Crossing a Ford

A line in long array where they wind betwixt green islands,

They take a serpentine course, their arms flash in the sun—hark to the musical

clank,

Behold the silvery river, in it the splashing horses loitering stop to drink,

Behold the brown-faced men, each group, each person a picture, the negligent

rest on the saddles,

Some emerge on the opposite bank, others are just entering the ford—while,

Scarlet and blue and snowy white,

The guidon flags flutter gayly in the wind.

Bivouac on a Mountain Side

I see before me now a traveling army halting,

Below a fertile valley spread, with barns and the orchards of summer,

Behind, the terraced sides of a mountain, abrupt, in places rising high,

Broken, with rocks, with clinging cedars, with tall shapes dingily seen,

The numerous camp-fires scatter’d near and far, some away up on the mountain,

The shadowy forms of men and horses, looming, large-sized, flickering,

And over all the sky—the sky! far, far out of reach, Studded, breaking out, the

eternal stars.

From the MSR Archives

Collected from the Library of Congress | Link to Source

Paul W. Bartlett, Walt Whitman, c. 1927, bronze, 9” d. GW Permanent Collection.

CONTEMPORARY RESPONSES TO THE CIVIL WAR

Collected from The George Washington University

Excerpt: Herman Melville and Walt Whitman both hold a place in the canon of American literature. Their works greatly inspired artists then and now. Their subjects were not always directly about the Civil War, but the upheaval of their subject matter and their writing style have been associated with the national unease which tore apart the nation and turned “brother against brother.”

This exhibit was originally shown in the Luther W. Brady Art Gallery 2nd floor cases April 9 – July 5, 2013. The exhibit was arranged in conjunction with the GW English Department’s conference “Melville and Whitman in Washington: The Civil War Years and After” June 4-7, 2013.

Whitman ref. begins at 1:18:30

Click here to skip to the relevant clip

Wide Awake

Performed by Bearded Ladies

at Washington College

An excerpt by Andrew Clements:

Paul Hindesmith

Paul Hindemith, composer

David Hoose, conductor

Boston University Symphony Orchestra | 2013

TEXT EXCERPTED FROM:

BU Today | Source

Commissioned in the wake of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death, composer Paul Hindemith’s 1946 work When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d (A Requiem for those we love) was based on the poem of the same title by the consummate American poet Walt Whitman. In setting to music Whitman’s poignant elegy for slain President Abraham Lincoln, the German-born Hindemith created what critics hailed as a profoundly American work. The BU Symphony Orchestra and Symphonic Chorus will perform the work tonight at Boston Symphony Hall, along with Charles Ives’ haunting Decoration Day, in the second of the College of Fine Arts two annual performances at the famed concert hall.

A stirring memorial to Roosevelt, who had worked tirelessly to ensure Allied victory in World War II, the composition was a labor of love for Hindemith. The composer had fled his native country in 1938 after the Nazi party condemned his modernist compositions as “degenerate.” Requiem was commissioned by conductor Robert Shaw (Hon.’94) just after FDR’s death in April 1945 and premiered a year later, with Shaw conducting.

In Requiem, Hindemith compressed Whitman’s 16-stanza poem into 11 movements for full symphonic chorus and orchestra, with the poet’s voice sung by a solo baritone. “Many years ago my mother told me the story of how she just broke down and wept as a young girl when FDR died,” says James Demler, a CFA assistant professor of music, who will sing the baritone solo. “When Hindemith was asked to write this music, it was with both Lincoln and Roosevelt in mind, and it was about how the nation was so deeply affected by those deaths. I’ll try not to lose sight of that when in performance.” Demler’s arias, some very complex, will be interwoven with that of mezzo-soprano Penelope Bitzas, a CFA associate professor of music, in the role of a thrush. In the poem Whitman implores the bird to “sing on, sing on” what he calls “death’s outlet song of life.”

“There’s a kind of nobility and melancholy within the text,” says David Hoose, a College of Fine Arts professor of music and orchestral conducting and director of orchestral activities, who will conduct the concert. “Throughout his Requiem, Hindemith, who died in 1963, captured the spirit that America aspired to at the time, and still aspires to today,” a “heartiness and sturdiness” that is reflected in Whitman’s poetry.

Collected from Boston University on Vimeo | Link to Source